What a thrill for me to have an opportunity to chat with illustrator Yas Imamura about our new book The Curious Life of Cecilia Payne (Eerdmans Books for Young Readers)!

Yas Imamura is an illustrator based in Portland, Oregon, working primarily in gouache and watercolour. She is best known for her work in children’s publishing, including Love in the Library by Maggie Tokuda-Hall and a Yoko Ono biography titled Can You Imagine? by Lisa Tolin.

Yas is represented by Susan Penny of the Bright Agency and has worked with publishers such as Simon and Schuster, HarperCollins, and Penguin Books. In addition to freelance illustration, she occasionally teaches as an adjunct faculty member at Pacific Northwest College of Art. Yas continues to contribute to the field of picture books and visual storytelling.

Laura: Thanks so much for taking the time to talk with me, Yas. The first thing I’m curious about is why you wanted to illustrate this story? Was there anything particular about Cecilia that attracted you?

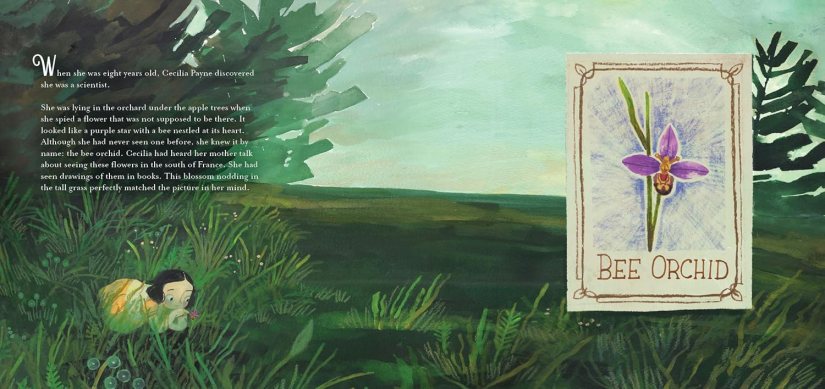

Yas: I was drawn to Cecilia Payne because of her quiet curiosity for things and how she observed patterns in the small things in nature and saw connections between a small flower in the garden and the cosmos. And to have to explored it as a child is even more intriguing to me. As an illustrator, I’m often interested in stories about people who see something others overlook. Cecilia’s inner life, her patience, her persistence, her sense of wonder, felt especially rich to explore visually.

Laura: The Curious Life of Cecilia Payne takes place in the early decades of the twentieth century. What sort of research did you do to help you capture the flavour of this particular time period? Does the setting of the story affect your choice of colour palette? You’ve done other books with historical settings. What is the hardest part of depicting a different time and place? What do you like best about it?

Yas: I looked closely at archival photographs, clothing, interiors, scientific tools, and everyday objects from the period… especially academic spaces and observatories. The setting absolutely influenced the palette. I leaned toward muted, atmospheric colours… smoky blues, sepias, soft greens… colours that feel slightly restrained but vibrant.

The hardest part of depicting a different era for this book specifically is perhaps just the scarcity of references and how to feel in the gaps between. What I like best is the constraint. Working within historical limits forces more intentional choices, and it often creates a quieter, more focused visual language.

Laura: Some of the key concepts in this story involve things that are either invisible or barely visible (e.g., the structure of atoms and absorption patterns in starlight). Was that difficult to conceptualize? Or did it give you scope to use your imagination? On the other hand, the illustrations also include lots of objects like notebooks and blackboards that are incredibly detailed. Those seem tricky too. What was the most challenging part of illustrating this story?

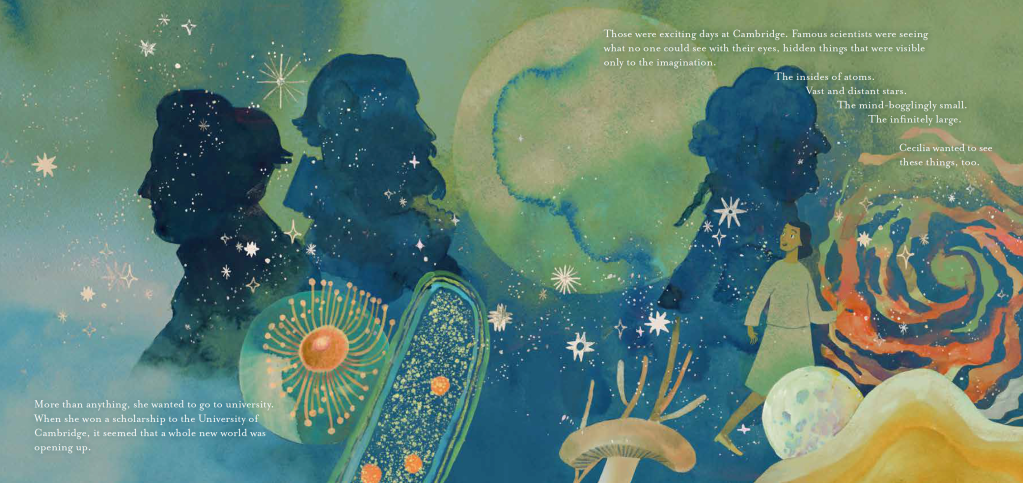

Yas: The invisible concepts were a little challenging but also freeing. There were definitely some diagrams I had to be more specific about but some of the spreads allowed me to move away from literal representation and toward metaphor. In contrast, the physical objects actually were a different kind of challenge but also just as enjoyable. The notebooks, chalkboards, and instruments required a bit of precision to ground the story in reality and credibility.

The most challenging part was balancing those two modes… the poetic and the concrete. Making sure the imaginative spreads didn’t float away from the story, and that the detailed spreads didn’t become stiff or overly instructional.

Laura: I laughed at the image of the rather pompous looking astronomer and his pointer. Do you always include a touch of humour in your illustrations?

Yas: I sure do! I’m glad you had a good laugh! I’m quite facetious about a lot of things also, so I often move towards humor even in unusual circumstances. It’s very natural for me to infuse it in most stories. I think humour is a form of honesty. Even serious spaces, especially serious spaces… contain absurdity. A touch of humour can deflate power without being cruel, and it can help young readers read social dynamics intuitively. I don’t force it into every illustration, but when it naturally emerges from character or situation, I lean into it!

Laura: Is there a spread (or even a detail) you find particularly satisfying?

Yas: There are one or two. I especially love the spread of Cecilia as a child observing the bee orchid… completely engrossed, quiet, and curious. That moment felt like an early echo of the scientist she would become. I also love the spread of her as an adult walking through the many figures whose work she built upon in astronomy. With that one, I really enjoyed playing with abstract scientific concepts through watercolor… letting the science feel expansive rather than literal. It was a spread where I felt free to explore, and I had a lot of fun with it.

And now Yas gets to ask the questions…

Yas: What first drew you to Cecilia Payne’s story, and why did you feel it was important to tell it for a young audience?

Laura: The first thing that drew me to Cecilia’s story was that moment when she lost confidence because senior astronomers questioned her research and conclusions. When we hear stories about extraordinary women in history, they are often portrayed as consistently fierce and strong. While Cecilia was undeniably both strong and courageous, she was also human. Most of us doubt ourselves at some point and Cecilia’s vulnerability made her feel more real to me. Also, she didn’t allow that stumble to define her. She got back up and kept going and that in itself is a powerful example of bravery and persistence.

I wanted to tell this story because I think kids (not just girls) will be inspired and encouraged by Cecilia as a person—her curiosity, determination, and ingenuity. The fact that she worked alongside a team of women a century ago is a pleasant surprise, and a great example of how science is collaborative.

Of course, I also want young readers to know what Cecilia discovered and its impact on astrophysics and our understanding of the universe. Stories of women in STEM have too often been forgotten or overlooked. Writing this book is my way of expanding the picture and helping young readers see that women can and do make profound and original contributions to science, now and in the past.

Yas: Cecilia Payne’s achievements were not fully recognized during her lifetime. How did you approach writing about institutional bias and inequality in a way that feels accessible to children?

Laura: Most children (especially elementary school age kids) have a very keen sense of what is fair and unfair. So rather than trying to point out and comment on the gender-based prejudice in Cecilia’s story, I simply made a few matter-of-fact statements (“some professors made her sit by herself”), then let kids draw their own conclusions.

Your illustrations help make the point. For example, when we see Cecilia sitting alone in the front row of a lecture hall with her books sliding off her lap and nowhere to write, while all the men in the class are at desks, the unfairness of it is clearer and feels more acute.

My hope is that young readers will notice these details and empathize with Cecilia. Perhaps then they will wonder why she was treated unfairly and how this was allowed to happen. I think kids are more likely to go in search of answers when the questions arise from their own observations.

Yas: Is there a line, scene, or idea in the book that you feel especially proud of?

Laura: One of my favourite lines is when the astronomer Arthur Eddington invites Cecilia to use the Cambridge Observatory library. “It was as if he had given her a key that unlocked the doors of the heavens.” Books are portals to other worlds. For Cecilia, having access to the thoughts, questions, and observations of great astronomers through history was life changing.

If you look carefully, you’ll see that I have dedicated The Curious Life of Cecilia Payne to my Auntie Marion and Uncle Winston, “who gave me books—keys that unlocked so many doors.”

I’m also proud of the back matter because I worked so hard on it, especially the spread called “Reaching for the Stars” which outlines some of the steps throughout history that led to Cecilia’s discovery. I wanted to show how, when it comes to human knowledge, we are always building on what comes before.

Yas: What kinds of stories are you most drawn to telling next?

Laura: Sometimes I think that writing is my way of figuring out how to live in this world. Lately I’ve found myself writing stories about creating and making (especially art and music) as an antidote to despair and destruction. I will always love writing about interesting lives; I have at least one biography out on submission (and a bunch more in a drawer). I also enjoy writing nonfiction picture books that focus on some aspect of the natural world and how we are part of its cycles. I’ve done this with photosynthesis (Sun in My Tummy) and the water cycle (Sea in My Cells) and have two more books along similar lines coming out in the next few years.

Thank you so much, Yas, for taking the time to talk with me about our book. It’s been a pleasure!

You can follow Yas on Instagram: @yas.imamura